Walter Neubronner was a proprietor of an undertaker firm throughout the period of the Japanese Occupation. Evidence of Neubronner’s work can be found as early as 1921, and up until 1960.

In the Double Tenth trial or Sumida Haruzo and others, Neubronner was a witness who provided an eyewitness account of a funeral he prepared for a European man, presumably Dr C. A. Stanley, a victim of the Double Tenth incident. During the Double Tenth incident on 10 October 1943, the Kempeitai arrested and tortured fifty-seven civilians and civilian internees. A total of 15 men were tortured to death, and one was sentenced to death. This incident happened due to the Kempeitai’s mistaken belief that the internees were involved in a sabotage mission on Japanese ships in Singapore Harbour. The mission was later established to be Operation Jaywick, a raid mission conducted by British and Australian commandos.

In November 1943, Neubronner was asked to make funeral arrangements by a Taiwanese Kempeitai, Toh Swee Koon, who called him from the YMCA building, the location of the Kempeitai headquarters. Toh told Neubronner that a Japanese high officer requested for funeral arrangements and brought him to meet the Japanese officer. Neubronner met this high officer, who he surmised to be Sumida Haruzo, the first defendant and Commander (Singapore Branch) of the 3rd Kempeitai Southern Army. Neubronner was asked to supply a coffin for the funeral of a European body that was lying in Kadang Kerbau Hospital. After telling the Japanese officer the price of the coffin and undertaker services, he went to see the body.

The European man, which Neubronner estimated to be about 45 to 46 years old, had no name on his body. Normally, the name of the deceased would be on the chest of the corpse for identification purposes. Neubronner noticed some blue marks on the man’s left and right cheeks. The right and left hands were also badly bruised. Toh told Neubronner that the man had died on the night of 29 November 1943.

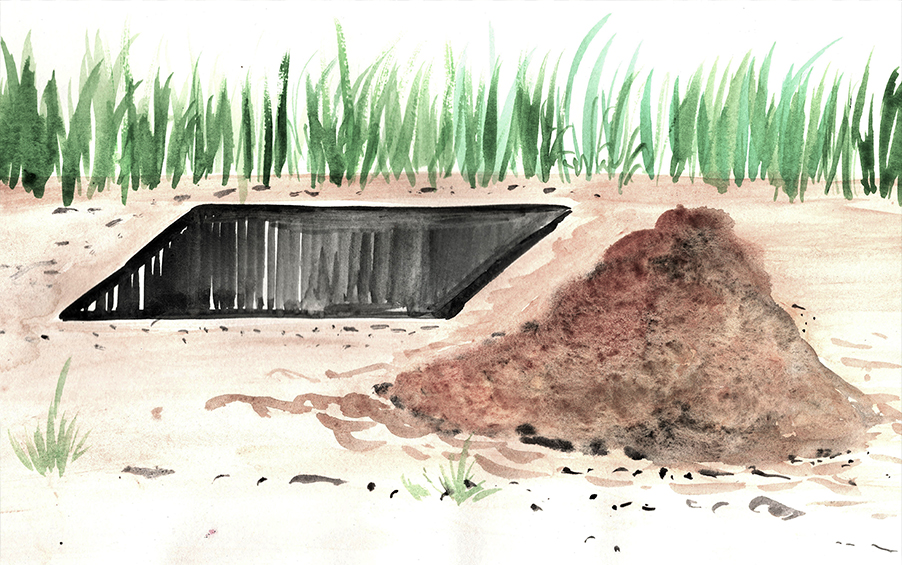

Neubronner took the coffin to the hospital the next day, and instead of screwing the coffin lif on, put nails into the coffin. This was requested by another Japanese officer, who Neubronner thought was the officer from Changi internment camp that was in charge of burying internees. The Japanese officers refused to identify the dead man, and the burial took place. Neubronner described that the “funeral was not performed in due style. It was performed like burying a dog and performed without a Minister.”

After an unspecified time from the day of the burial had passed, a gentleman called Neubronner’s office and asked if he had buried “Dr Stanley”. Neubronner was unsure, but informed the gentleman that he buried a European man, and gave the description of the dead man to the gentleman. The gentleman told Neubronner that he was Dr Stanley’s father in law, and confirmed that the dead man to be Dr Stanley after hearing Neubronner’s description.

At the Double Tenth Trial, Neubronner also testified to the court what the mortuary was like, and the other bodies he saw there – bodies of children, and another Chinese man. Neubronner’s testimony was featured in the Straits Times.

After the war, Neubronner continued his business as an undertaker. He was successful in his business and a public figure: his family picture was published in The Straits Times on his 31st wedding anniversary, and his 34th wedding anniversary in 1951 was publicised on the Sunday Standard. Mr and Mrs Neubronner were also featured by the Straits Times in 1960 for 43 years of “true love”.

Neubronner also made a name for himself post-war as a private detective. He conducted private investigations into multiple divorce cases. He was often featured in the papers for catching bicycle thieves, helping the police break up a secret society attack, and even chased and caught a man who had attempted extortion with a hand-grenade.

Neubronner was hailed as a “fine example” of citizenship. He received awards from the Chief Justice and government for his services in preventing crime, including a commendation letter, a silver coffee set, and monies. Apart from receiving significant attention from the public authorities, Neubronner was also visited by thugs and purportedly, gang spies.